To Future Nights

In our WrightSpace program last December Scott Button worked with dramaturg Joanna Garfinkel on development of the audio drama version of his play Night Passing, which has just been released as part of Arts Club Theatre’s Listen to This: Audio Plays series. In writing his playwright’s note for the Arts Club, Scott found himself writing an essay about historical narratives, queer narratives in particular, in view of the fact that Night Passing was inspired by the true stories of LGBTQ+ Canadians who endured brutal harassment at the hands of their own government, and the vital resistance that followed. This piece was first published as a Note from the Playwright on artsclub.com and on Scott’s website, scottbutton.ca

The present is not enough. It is impoverished and toxic for queers and other people who do not feel the privilege of majoritarian belonging, normative tastes, and “rational” expectations…. The present must be known in relation to the alternative temporal and spatial maps provided by a perception of past and future affective worlds.

—José Esteban Muñoz (1967–2013), Cruising Utopia

TANYA [played by Marlene Dietrich]: He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?

—Touch of Evil (1958, screenplay by Orson Welles, novel by Whit Masterson)

Night Passing was originally conceived as a play for the stage and was nourished by the Emerging Playwrights’ Unit at the Arts Club in 2019. I adapted it into a television pilot script that year, and now it has arrived as a narrative podcast. I think the story is truly at home in the form of an audio drama. Far less prescriptive than theatre, and certainly less so than television, audio drama conjures images and story only with the enthusiastic consent of the listener. I am excited for you to be transported to the Ottawa of 1958, hearing the world that Elliot is crafting for you alone, casting you in the dual role of confidant and voyeur.

I don’t think it’s necessary to state the importance of excavating history. In fact, the “importance of revisiting history” argument has often been used to justify art that damages. Shrouded in seriousness, works set in the past have been used to propagandize and rewrite historical accounts. The shameful Stonewall (2015) film, for instance, portrays young, white cisgender gays being among the ones to throw the first bricks in New York in 1969. That’s far from true. It was the queers of colour, the trans women, and drag queens who put themselves at the most severe risk of harm from the NYPD that night in 1969, and who continue to do so to this day. In fact, it was the white cis-gays who were the first to turn away and distance themselves from “extreme” activists like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera (for more on these icons, check out this article by Ishmael Bishop). As a queer, white, cisgender male, I am beneficiary to countless privileges that those queens fought for. Privilege works like anaesthetic; it can make you feel cozy, numb, and forgetful. With that in mind, historically set art offers a compelling imperative: an antidote to forgetting.

historically set art offers a compelling imperative: an antidote to forgetting

Throughout working on Night Passing, I have been considering the baggage that all historically set work carries. As I note above, there is a very-much-alive tradition of culturally dominant artists (white, cis, usually male, and often straight) who attach themselves to historical content centred around marginalized groups. This isn’t limited to Hollywood movies, by the way; this is endemic to many art forms. Dominant artists can extract profit and prestige from such projects and, even more frequently and subtly, use the lived or inherited histories of non-dominant communities to “inspire” and “diversify” their own work.

Despite this baggage, something keeps bringing me, and so many of us, to works set in the past. History continues to fascinate, revolt, and instruct us, and because of this there will always be a yearning for work set before the immediate present. By tapping into nostalgia or animating an era distant to us, these stories touch us in ways that contemporary-set work cannot. In addition to offering an antidote to forgetting, historical work can have a refracting quality—it enlarges our present selves, and also, by looking to the past, we feel a pull to consider the future.

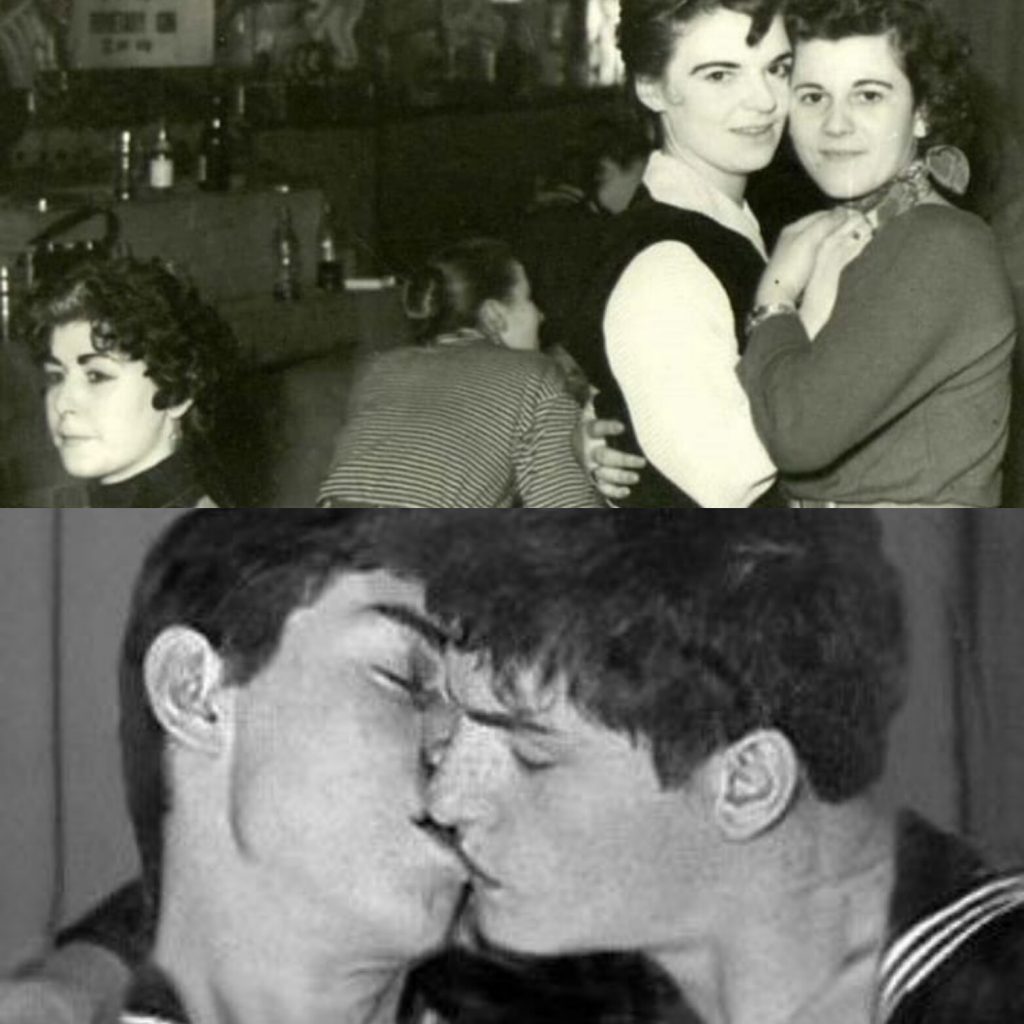

When I was researching the RCMP’s state-mandated war against LGBTQ2S+ people, which lasted for decades, the era’s bleakness made it tempting to craft a story loaded with trauma. But that would be a shallow analysis of queer history. To be sure, the 1950s were horrific for anyone who wasn’t part of the dominant homogeneous culture, and queer people had a famously difficult time. Vicious outings and sodomy laws contributed to a life of rigid assimilation for even the most privileged gay people. Meanwhile, queers of colour waged a two-front war: the fight for their fundamental human rights, as well as the search for safe places to love each other. For queers of colour all over the world, particularly for trans and gender non-conforming folks, these battles are still being waged today.

Yet, during my research on the queer purge, other truths emerged. Not ones centred on brutality and self-betrayals. Instead, I found stories of love, of naughtiness and fun, of vitality and resistance. These are also queer histories that mattered; they should also be remembered.

In approaching such a loaded historical moment, using genre as a framework made sense to me. Many of us know the tropes of film noir—the fashions, the shadows, the jazz—even if we don’t have direct experience with the genre itself. In film noir, the characters are, broadly speaking, archetypes. These people know who they are in the world, there is a built-in sense of irony to the femme fatale, the corrupt cop. This wry self-awareness reminds me of the state of inherent irony that queer people inhabit in straight society. Anyone who lives outside of the dominant homogeneous majority demonstrates this social irony: an awareness of the performativity of all actions of being, most of our daily life made up of a conscious choice to submit to the spectrum of assimilation—or to resist.

I dedicate Night Passing to queers of the past and of the future. As José Esteban Muñoz argues in Cruising Utopia, LGBTQ2S+ folks of right now must always have an eye both in front of and behind us—to the queers who loved and fought for our present selves, and the ones who will carry the torch to a more expansive future.

Acknowledgments

I am truly grateful to the Arts Club for investing in Night Passing—during its development in the Emerging Playwrights’ Unit in 2019, and now as an audio-drama in the company’s season of works. Particular thanks go to Stephen Drover, Rachel Peake, and Ashlie Corcoran, all of whom offered sharp insights and were instrumental in shaping the piece. Ashlie also directed Night Passing, and I am grateful for her acute eye (and ear!) in perceiving all the dimensions of the story. There are so many more folks to thank at the Arts Club, but I’ll simply say that I am deeply appreciative that the company has ushered a new queer work into being and given it such a platform.

Thank you to the BC Arts Council and the Playwrights Theatre Centre who were crucial in assisting the project’s development. Sincere thanks are owed to Joanna Garfinkel. Joanna offered dramaturgy for two significant development periods. We would compare notes about the film noirs we were watching; her investment in the project (and all of the work she does!) always moved me. She is not only a rigorous collaborator but has also been an ally throughout the life of the work, and I am very grateful.

Heartfelt thanks to the artists, technicians, and staff who have brought the Night Passing audio drama to life and those who have assisted in its development to this point. Thank you to Mathieu Aubin for generously offering historical context.

My sincere thanks to the LGBTQ2S+ folks who generously shared their personal stories with me. This was vital in the early stages of developing Night Passing, and those stories will stay with me forever.

Lastly, I want to acknowledge my spouse, Chris. Thank you for reading (too many) drafts and promising me that some day it might be worth it. I am beyond lucky to have your unwavering support and kindness. My past, present, and future self is enmeshed and in love with you.

—Scott Button

For more information on the Canadian LGBTQ+ purge, click here.

Worthwhile causes to support:

Urban Native Youth Association’s 2-Spirit Collective

QMUNITY – BC’s Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit Resource Centre