Joanna Garfinkel on how Japanese Problem changed her life

In September 2020, before Kathleen Flaherty emptied her desk at PTC, she engaged incoming Dramaturg, Creative Engagement Joanna Garfinkel on the subject of Japanese Problem. In the days after experiencing Japanese Problem at the barns at Hastings Park, Kathleen had heard from Joanna that the piece that Universal Limited created on the subject of the Japanese Canadian incarceration during WW2 had significantly steered her dramaturgical practice going forward. Naturally, she wanted to know more.

KF: I want to talk today about Japanese Problem and how it changed your life. Can you describe Japanese Problem for us? How it turned out and how it was developed.

JG: I think I’ll mention how it started, because I think that’s a good way to talk about how the piece is. Yoshie Bancroft [JG’s partner in Universal Limited] went on an historical tour of Japanese Canadian sites of significance, I believe in 2015, and it included a tour of the barn at Hastings Park, now the PNE, where citizens were incarcerated for being Japanese Canadian during WW2. There was no marker inside the barn, there was no mention of the historical atrocity that happened there. And after she went on this tour, she was so moved by the experience, but also the lack of acknowledgement of the site, the juxtaposition of what had happened there and how little people knew of it, and it seemed very much like the kind of work we make in our theatre company so she said, “Do you think we could do a piece there, about this?” And, my luck was saying “Yes, I think that’s an amazing idea.”

“…the government’s intention was to split people up, to prevent there from being Japanese Canadian neighbourhoods, to culturally and otherwise assimilate people. That was their solution to the ‘Japanese Problem’– the title that was derived from documents of the time that our government put out.”

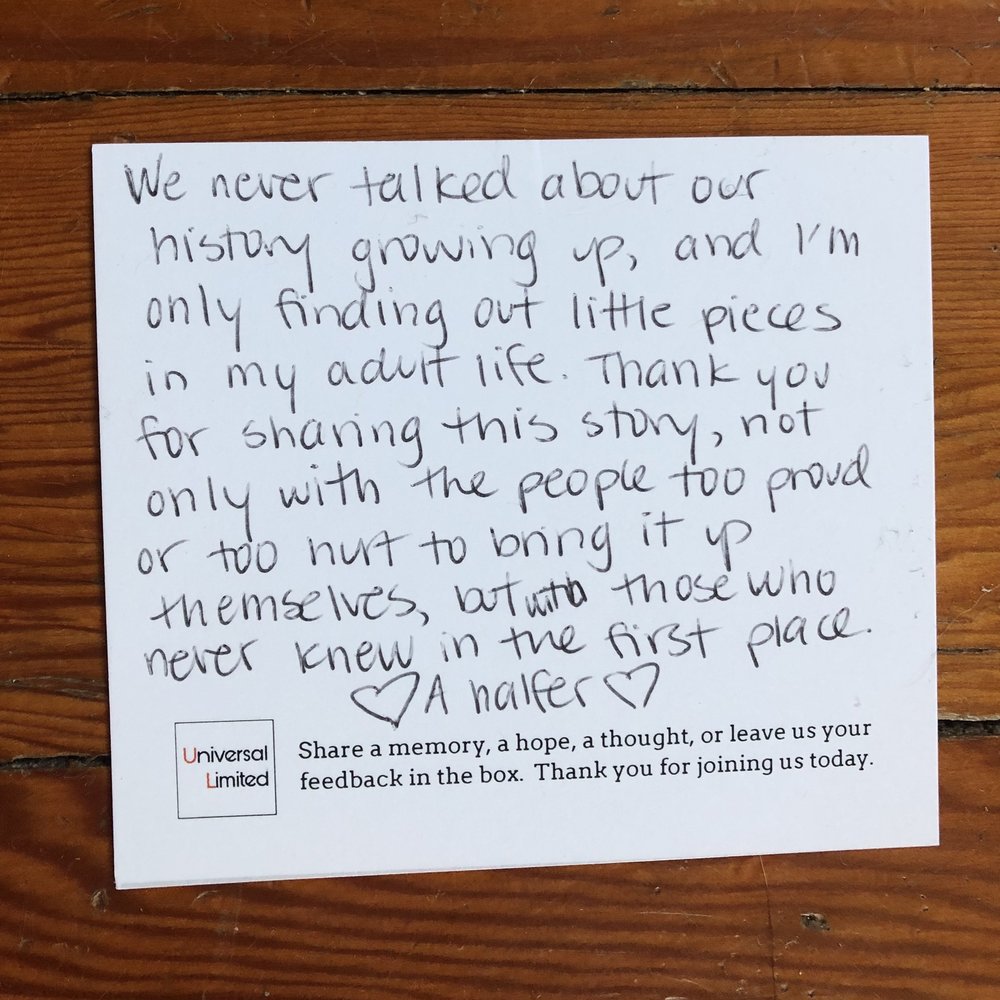

We didn’t really know how we were going to figure it out. We started doing research just on our own and that site was, at the time, poorly protected, so we could just wander in and look at it. And we did. A lot of times. I did a lot of historical research. And we started getting connected with other activists – there’s this committee called The Hastings Park Committee that we joined which is largely survivors and children of survivors looking to find justice for what happened. And the more research we did, the more it seemed like the perfect locus to discuss the incarceration of Japanese Canadians during WW2 because Hastings Park served as a sorting centre, so it was both a place where people lived, but it was also a place where people were processed to figure out where they would go next, whether it was to incarceration camps in the interior, whether it was to beet farms in the prairies, whether it was people who were sent to Japan, even though they’d never been to Japan. So, by investigating the stories of the people who had been at Hastings Park, we realized you could tell a lot of the stories of incarceration. But not just the incarceration, not just the historical artifact, because the thing that became clear was that the generation of Japanese Canadians that were between Yoshie’s age and my age, have a very specific kind of intergenerational trauma, because culturally, micro-culturally and macro-culturally there has been a culture of not talking about it, whether macro-culture in the way that the Canadian government and the BC government has hidden many of the terrible things they’ve done, but microculturally in the way that families were so…. there were so many forces of assimilation…. the government’s intention was to split people up, to prevent there from being Japanese Canadian neighbourhoods, to culturally and otherwise assimilate people. That was their solution to the “Japanese Problem”– the title that was derived from documents of the time that our government put out.

The place became really fascinating to us because so many stories converged there. And then, as we started the more formalized process, we became focused on the multigenerational effects. I’m not Japanese Canadian. All my grandparents escaped from the Holocaust, which felt like a parallel kind of trauma that people my age are dealing with, a different thing that my grandparents didn’t really talk about. And somehow having that parallel history helped when we started to go on our formal research, to interview survivors and also descendants of survivors. There was something about that kind of shared experience as an entry point to conversation. So that’s kind of the back story.

“I guess one of the ways that that piece changed my life was that no theatre company would agree to do it with us early on, so we knew we were on our own.”

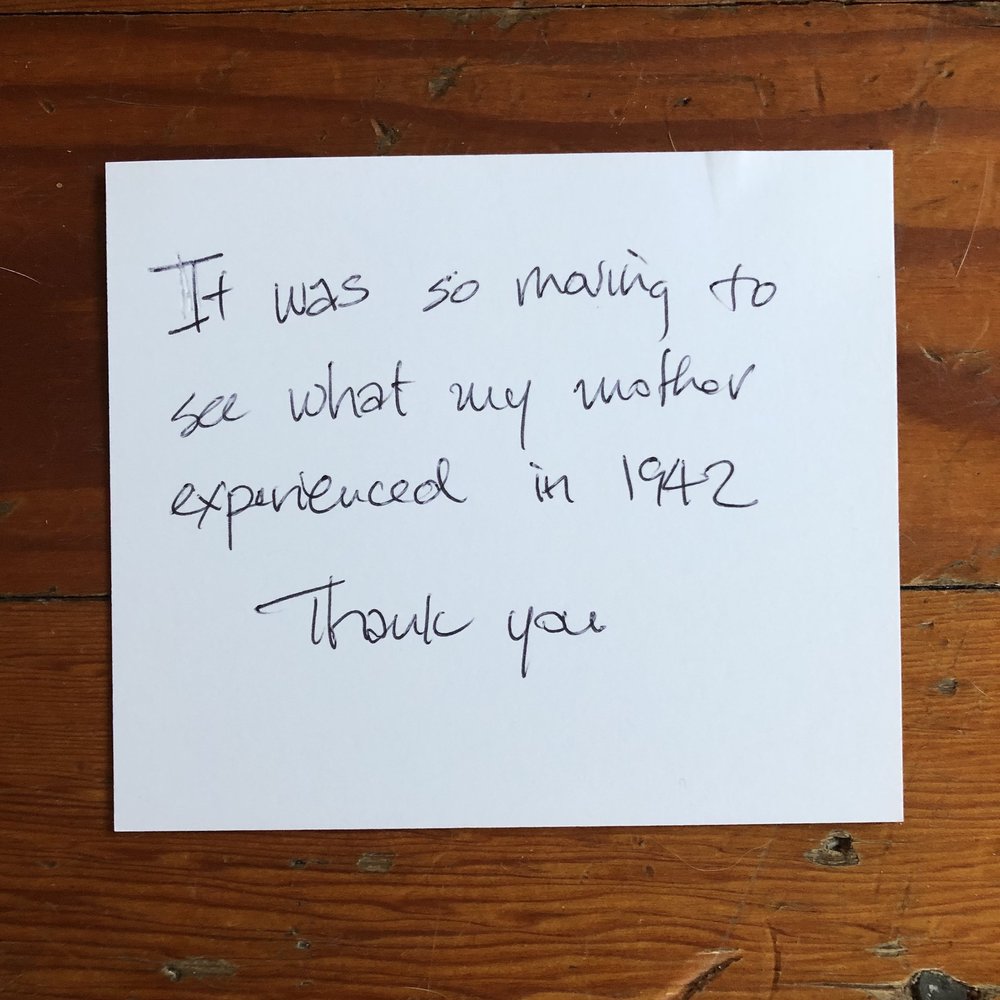

But what is the piece like? We built it so that it would be not just site-specific to Hastings Park but also so we could travel it. Because as we started to build it, we knew we wanted to move it around. We wanted it to be site responsive, never in a formal theatre situation. We knew that the conversation in and around it was in many ways as important as the piece. And I guess one of the ways that that piece changed my life was that no theatre company would agree to do it with us early on, so we knew we were on our own. At every turn we were able to decide to do something for the health and well-being of either the participants or the audience. At a very early point we decided that we would not centre whiteness. I feel like so many stories of exclusion, especially racialized exclusion in Canadian theatre, are imagining that the audience is an upper class white older person, and it’s a very othering portrayal of what’s happened. We were wanting to speak to the community, especially reflecting all the ways that people were trafficked across the country. And when we did a very early version at the Powell St. Festival, it became very clear that the audience wanted to interact with the piece. And because it was site-responsive and people moved through it, that was intentional, and that intentionality started to expand. We had hoped people would contribute their feelings, but also if they didn’t want to speak, they could write them, too, and we started to have discussion circles that ultimately led to these specific encounters led by a counsellor for everybody’s safety. We created ways that people could share stories, especially since that act of sharing stories had been denied for so long.

KF: Can you get into more detail of what differences you observe in the work when you don’t centre whiteness?

JG: So, we knew that we were going to tell the stories from the perspective of Japanese Canadians. That’s one way that you don’t centre whiteness. A classic structure of centring whiteness would be showing the experience of a racialized community, but the protagonist is a white person who comes in and says, “What’s this?” or Schindler’s List or whatever, the white savior, or what is considered to be human neutral… I do not share that vision… but we’ve been told for so long that Human Neutral comes in and says, “Oh, the Horror! I cannot believe this! I’ll help you lovely people!” And that is a classic example of centring whiteness. We do have a white character in the story for a bunch of reasons, but that character is not the protagonist, that character doesn’t save anyone, that character doesn’t even interact with everyone except for one moment, you know? He doesn’t really witness what is truly happening because he represents mostly what we found when we researched it, which was white people mostly knowing [what was happening], with a twinge of “This doesn’t feel right. But there was a war.” Our white character represents the preponderance of stories that we read, about us not doing something.

As white people, we like to think, “If we were there, we would have been fighting it.” Statistically, that’s very very unlikely. Statistically, very few white people fought it. I found in one archive one tiny protest pamphlet that’s a beautiful document, but it didn’t seem to gain much traction. And BC was the worst; BC kept incarcerating people long after the war, until ’49, and some people didn’t have the right of return until ’51 or ’53. And so, to be like “I’d have been the magical white person who would have changed things,” is unlikely. Like when I went to Eastern Europe to do some research about my own family when I was in my 20s, I met a man in Warsaw who said, “My family saved yours.” On a certain level I was like, “Then why are there no Jews here? If everyone was so good at saving us, why are there none of us here?” So, there’s no one like that.

” …when you walk into the barns, you are hit with the smell of shit, you are hit with the smell of animals, and that is exactly what the citizens of Canada who were hauled in from their homes and apartments and farms and so forth would have felt.”

And because we had so much early support from the Japanese Canadian community and so little early support from the theatre and “traditional theatre-going community”, we wanted to speak to the Japanese Canadian community first and then everyone else.

Once we started having the piece in the barns particularly, the way that scheduling worked, we were wanting to coincide with an historically significant anniversary in 2017, in September, right after the PNE ended. So that when you walk into the barns, you are hit with the smell of shit, you are hit with the smell of animals, and that is exactly what the citizens of Canada who were hauled in from their homes and apartments and farms and so forth would have felt. And you’re instantly hit by this cold and wet and unpleasant and unhealthy place. An unhealthy place with the troughs for open sewage to rush by your feet and those brutal inhumane conditions all still in place. It’s a very visceral experience. When we do the piece in other places that aren’t so literally filled with shit, it’s still a good piece… like we did it in Steveston at a cannery where a lot of Japanese Canadians workers and employees were taken, we did it in Kaslo in a building where incarcerations had happened, and those places are historically significant, but when you walk into the barns, there is something very visceral. And when we first made the piece, we really didn’t think many people would turn up to it – to go to a rainy barn that smells disgusting, that’s not an easy place to get to, or a typical place to see art. For many reasons we made it pay what you can afford, for many reasons we made it for the community, to address, confront, deal with things that aren’t really talked about. It wasn’t necessarily built to be a theatrical success.

KF: Well, it was a very powerful experience for me, a white person, so I can only imagine how powerful it was for the community. It was a very significant piece, so you can probably talk about it forever, but you did once say that it changed your approach to dramaturgy and I’d love to hear more about that.

JG: I’ll try to narrow it down. (laughs) One of the things is, being far enough along in my work to know to listen to my intuition and to stop and respond to what’s happening. To notice what’s happening and to respond to what’s happening. And that the dramaturgy continues and the piece continues evolving. There’s no end point, it’s not finished. That’s a key component of that piece – it’s continually re-investigated, every single time we’ve done it, and we’ve done it many times…continually dramaturgically intervened as we started to formalize our practices.

We noticed the way that people attending it at Powell Street, the early 15-minute version that we did, the discussion was important, people didn’t want to leave… because at Powell Street we were supposed to do six a day, something bananas, but they were short. But people didn’t want to leave. They kept wanting to talk to us. That was a simple thing to notice, you know, “we need to build in more time because people don’t want to leave; they want to keep talking to us. And we don’t want to feel compelled to kick them out and rush into our next show.” We were scheduling them the way we had scheduled our previous piece, called “Tour,” which was, we do one and we need fifteen minutes to re-set and then we’ll do another.

“Dramaturgically, one thing you can do is to have a land acknowledgement before a piece. But for Japanese Problem, the land acknowledgement is in the piece.”

Also, at all those discussions after, we would learn a bunch of new things because all this history hadn’t been recorded. On one of our research trips to the interior, there was this archive of unpublished first-person accounts that somebody did… someone got a small grant and recorded these stories, but they aren’t published anywhere. So many stories that we were receiving aren’t kept anywhere, so every time someone would tell us something, we’d want to include it.

One of the rules of the piece was, “Every line is true.” Every single line comes from a piece of historical research, a piece of interview, every line is referencing something, but the characters, in many ways, they are fictional. They are constructed. But they are constructed from these facts. It allowed us a freedom rather than having to do a faithful reproduction of one human history. Also, each of the performers had worked their own history in. I can give you an example. Dramaturgically, one thing you can do is to have a land acknowledgement before a piece. But for Japanese Problem, the land acknowledgement is in the piece. It’s part of the history that one of the characters tells you; it’s woven into the characters talking about how the Canadian government uprooted Indigenous keepers of the land, only to then force Japanese Canadians into those very same places. And each of the company members, how they got here, is directly related to that history. Each of the characters is themself, the actor. And we decided that we didn’t want anything separate. We didn’t want a “curtain speech” because there is no curtain really…well, there’s a kind of a curtain, a dirty bedsheet.

There’s a way to talk about how you take care of an audience, they are always accompanied, there is always a guide they can look to, they are never left alone in a scary location, they are always taken care of. And we also listen to them, we respond to the things that they say. And many of them become a part of the piece as it moves on. It’s a living document. If we end up doing it again, I’m not sure what will happen. You may have seen, but somebody recently brought up a suggestion that because of all the encampments that have been popping up because so many people are unhomed and unhoused in this wealthy city, “why don’t we house some people in Hastings Park?”

KF: Whoa.

JG: The concept that our city was, that this atrocity that was performed on what was then the city’s most unwanted citizens, would now be repeated on what are currently the city’s most unwanted citizens is not lost on me. Maybe it’s a contest over who are the city’s most unwanted citizens. But the idea that they are trotting out this idea again. And there was also this big kerfuffle that the PNE is suffering financially because of the lockdown and what if we lose the space. And that space is haunted. It’s the haunted site of so much wrongdoing. Part of me is like, “Burn it down and put up a monument.” It’s so Canadian to me – that space has so much wrongdoing but no recognition. I saw Auschwitz when I was on that trip to Poland in my twenties – there’s a mark, there’s a sign of what happened there. It’s so Canadian to have a site in the middle of our city that just sits there, that only in recent years has had external signs detailing a portion of the history.

KF: Because no one knows about it.

JG: It’s a circle, right?

KF: It’s a very common circle that we leave behind our history.

JG: And many Indigenous folks who went to JP left comments like that on the cards. “This is so Canadian. If we don’t acknowledge it, if we bury it, it will go away.” And our government did this with residential schools. They did this with other sites of historical wrongdoing. If we hide it, it will be like it never happened, we can continue with the narrative. When we started with this work, many educated, largely white but not exclusively white people, many people who were not Japanese Canadians would say to me, “Oh yeah, that was really bad, but it was worse in the United States.”

KF: We do that all the time.

JG: It’s not a contest. But no, it was worse here. Factually, statistically, any way you want to slice it, it was worse here. In the US, many people got their homes back, even though things had been stolen from them. Not everybody did. But here, the Canadian government took everybody’s property, their homes, their bikes, their dishes…. they took every item and auctioned it off to supposedly pay for the incarceration. So people had nothing to come back to. Not only that, but can you imagine if you had a little bungalow in Marpole, your grandparents did, what that would do for your family? Owning land, it’s very complicated, but we did talk a lot about the stuff, because the stuff, the stealing of bikes, the stealing of cars, the stealing of bed linens, no item was too small for the RCMP to confiscate and sell off. You can get much better data from Landscapes of Injustice, which is an amazing project that is partially an academic one that is trying to calculate the amount of loss. landscapesofinjustice.com

KF: How do you navigate your emotional reaction to the content while trying to steer the piece for its efficacy and safety for the audience? I’m not saying that we don’t all get emotionally involved in our work, but sometimes as a dramaturg, the more emotionally involved I am, the less likely I am to be helpful.

“I think that one of the ways that it changed my life, one of the ways that it changed my professional life anyway, was seeing that you need to build a process for that emotional material.”

JG: That’s an interesting question. I use those emotional reactions especially during the research phase when you get a visceral reaction… you’re paging through stories and you read one and you get a visceral reaction, “Oh man, that needs to be included.” We collected piles of information and we shared it with our collaborators and that’s when the collaborators started to kick in, and I started to build composition exercises in the studio. So I had already had my emotional phase. I’d had my emotional phase in dusty archives, basements in the interior. I’m now in the phase of watching other people assimilate this information. Because of the time, what do they call that, the logarithmic nature of time, I’m already inured to the emotional reaction by the time the collaborators get to it. And by the time the audience gets to it….okay, I’m not inured, I don’t have a lump of coal where a heart should be. I know I was the only audience shepherd for this piece, but the training for being the audience shepherd includes a lot of small and large decisions, hopefully invisible, that I make to protect an audience In the moment. I don’t watch the show like an audience at that point. I watch the audience to make sure that everyone’s okay.

I think that one of the ways that it changed my life, one of the ways that it changed my professional life anyway, was seeing that you need to build a process for that emotional material. I don’t care if typically plays are built a certain way, I don’t care that then they’re done and they have an author written on them and then they’re sent to various theatre companies. That will never work with this. We do it and we’re in charge of it. Now because there’s been some lovely support and we’ve built a process, we’re able to do it. We are still able to have rigour and structure, rigour and structure that supports the actors and protects the audience, things that allow it to have a beginning, middle and end, a full complete experience, not just stories that make you sad, that are presented in no order. I think that those are some of the lessons that I’ve taken into other projects that are perhaps more traditional.

KF: Thank you very much.